AGNIESZKA KURANT: RECURSION

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY is pleased to present Recursion, Agnieszka Kurant’s second solo exhibition with the gallery, on view from 6 February to 21 March 2026. The exhibition brings together new and recent works—speculative thought experiments developed in collaboration with scientists, linguists, engineers, and philosophers.

February 06 - March 21, 2026

Kurant’s conceptual practice investigates collective and nonhuman intelligences, the future of labor and creativity, and forms of exploitation embedded in digital capitalism. Her work examines how forms such as termite mounds, tools, languages, and social movements emerge through collective agency. In the complex systems she creates, molecules, bacteria, animals, AI algorithms, and human crowds interact to generate unstable, hybrid forms in constant transformation, like living organisms. Her projects draw on automation, cybernetics, and the processes of networked value creation in the digital economy and address the global labor extraction underlying artificial intelligence. Grown or shaped at the molecular level, her works oscillate between biological and digital, natural and artificial, life and nonlife.

The exhibition examines how digital capitalism converts human culture into a reservoir of data and renders us all part of a network of vast, recursive machines. Corporations such as Google absorb and recompute user data within feedback systems that forecast behavior; automate decisions; and preempt, monetize, and weaponize probabilistic futures. These processes in turn transform the human mind and the collective unconscious. Recursion emphasizes how forecasting the future can actively shape it.

Kurant’s works draw on recursive and self-organizing phenomena, ranging from the biological evolution of living systems to brains, languages, social organizations, currencies, markets, and states. The artist investigates the recursive nature of digital images as “metabolic media”[1] eating the future: scraped, recomputed, and folded back into AI systems, these images extract energy, labor, and attention to train predictive algorithms in an endless feedback loop.

On the gallery’s street-level window is Future (Invention), 2024/2026, a constellation of the word future translated into fourteen languages. The work explores how different cultures spatially conceive of futurity: speakers of Aymara, Māori, Darija, Malagasy, and Yupno understand the future as coming from behind, above, or below—rather than lying ahead, as in dominant Western worldviews. The installation highlights how language shapes our thinking and invites viewers to imagine futures grounded in other cosmologies. The work references America Invention (1993) by artist Lothar Baumgarten.

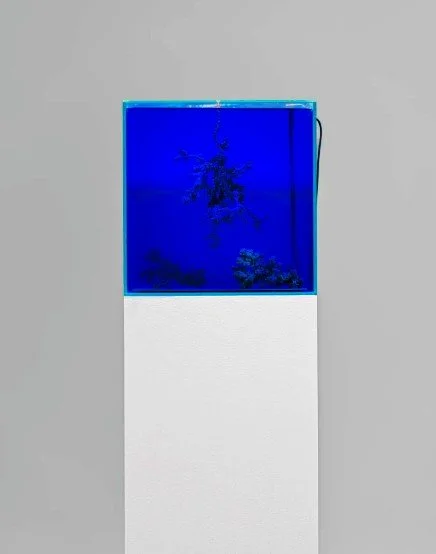

At the center of the exhibition are Uncomputables (2026), an installation, and Unthoughtforms (2026), a set of suspended sculptures. Both are inspired by the experiments of British cybernetician Gordon Pask, who believed living systems can solve problems in ways that exceed human thinking. Pask developed “chemical computers”—electrochemical systems that modeled aspects of the brain and social organizations. He conceived computational problem-solving as a physical process in which solutions emerge through chemical interactions rather than abstract calculations. In his experiments, he grew metal crystals in copper sulfate solutions by passing electric currents through electrodes to form branching filaments in self-organizing feedback systems. Kurant reactivates these experiments in an aquarium where metal, tree-like forms grow in response to AI-harvested real-world socio-political and economic data, which are parsed and converted into electric current flows and sound vibrations by a computer-controlled system. Each structure records an emergent idea or solution as a physical abstract form—a crystallization of something yet unthought.

Recursivity, 2024/2026, presents a chameleon inside a terrarium whose glass panes are replaced by mirrors. Cast in bronze and coated with liquid crystals—a material used in LCD screens that fluctuates between states of matter—the sculpture draws on a riddle posed by Stewart Brand to cybernetician Gregory Bateson in 1973: What would a chameleon do when confronted with its own reflection? Here, the chameleon’s skin pigmentation is altered by a custom AI system that processes data from millions of social-media users speculating about the future and converts it into thermal and electrical signals. The work stages a perpetual mirror test, involving viewers in a recursive loop of looking and data production and reflects humanity’s entanglement in shaping, and being shaped by, its own predictions of the future.

Alien Internet, 2023/2026, features a shape-shifting cybernetic organism animated within an electromagnetic field. The work uses ferrofluid, a material developed for NASA in 1963, whose tiny magnetic particles lend it the properties of multiple states of matter. The evolving quasi-life-form is continuously reshaped by behavioral data (e.g., migrations) from millions of wild animals, including whales, bats, elephants, and sponges. This data, tracked globally through digital technologies (including AI, GPS, drones, and remote sensing), is used to predict earthquakes, pandemics, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions, resulting in a planetary sensing surveillance system. Alien Internet conceives of millions of nonhuman organisms mutating into a single, sentient communication network, a collective biological computer-mind.

Adjacent Possible, 2021, explores alternative evolutionary paths of human culture by fusing Paleolithic technologies with artificial intelligence. Kurant collaborated with paleoanthropologist Genevieve von Petzinger and computational social scientist Justin Lane to train an AI algorithm on thousands of Paleolithic graphic signs that, dating from 40,000 BC to 14,000 BC, make up the earliest known forms of symbolic communication. The algorithm then generated new signs that could have emerged from the same collective subjectivity. To inscribe these signs on stone, Kurant worked with a synthetic biologist and used pigments produced by genetically engineered bacteria and fungi, an homage to the “living pigments” of the Gwion Gwion rock paintings in Australia preserved over 40,000 years by microbial activity.